Ever since its release, The Kashmir Files has taken India by storm, after a 32-year-long, deafening quiet on the plight of Kashmiri Pandits.

As the film rehashes forgotten history and scrapes out old skeletons, the country has erupted in an extensive debate of political correctness and blame-game.

Why Has The Film Caused Unrest?

Well before the domestic or international release of The Kashmir Files, filmmaker Vivek Agnihotri and his wife Pallavi Joshi, who plays a vital character in the film, managed to attain a fatwā against themselves in Kashmir as shooting for the last scene progressed. Following its international release and condonement, some political groups and their supporters, along with the Muslim community, have been wary of its domestic release. Last Tuesday, on March 8, the Bombay High Court dismissed a public interest litigation (PIL) demanding a stay on the film’s release, filed by one Intezar Hussain Sayed from Uttar Pradesh. The petitioner had filed the PIL after the trailer was released, and argued, “It is clearly evident that the whole movie will also be portraying in a targeted one-side view of the incident which is not only hurting the religious sentiments of Muslim community but also ignite emotions and inflame the members in Hindu Community with clear possibility of triggering violence immeasurable destruction in all the active parts of India.” His petition further read, “A person cannot exercise his/her basic fundamental right while violating fundamental right of another. The movie is clearly a propaganda piece and is not an artistic expression of any event but a one-sided inflammatory incendiary work.”

While ruling on the matter, the Bench noted that the ‘A’ censor certificate issued by the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC), had not been challenged by the petitioner, even though the rule of exhaustion is applied.

The film also explores the academic side, and the rampant misinformation spread when it comes to Kashmir. The timing and intention of this movie and its makers have also been questioned since it was initially slated to release right before election season.

Political Debate & Historical Evidence

A series of tweets by Congress Kerala, some of which have now been deleted, upset a lot of people including the persecuted community of Kashmiri Pandits whose plight has been highlighted in the film. In one of the tweets, the organisation wrote, “For BJP, #Kashmir is a Hindu-Muslim problem. For Congress, it’s a long battle between separatists & those who stand with India. Let’s respect ALL Kashmiris who’ve made sacrifices in this battle. Congress brought peace & rehabilitated victims. BJP ruined it for politics.” In another tweet, they wrote, “After the terrorist attacks, instead of providing Pandits security, BJP’s own governor Jagmohan asked them to relocate to Jammu. A large number of Pandit families did not feel secure and left the valley in fear.”

As per first person accounts of several Kashmiri Pandits who fled at the time, the community strongly believes that the only reason they could get out of Kashmir was because Governor Jagmohan Malhotra provided them with safe passage. Recollecting the events, one of the sources who was in Srinagar with her family at the time, says, “After the CM (National Conference leader Farooq Abdullah) resigned on 18th evening, we knew it was time to go. The mosques were echoing, asking Kashmiri Pandit men to either convert or leave the valley and ‘their women’ behind. Mujahideen posters saying the same were posted outside every Hindu house. There were so many disappearances and killings of both community members and army personnel… resounding automatic weapons… we knew we couldn’t trust anyone. Nai Sadak (area in Srinagar) was a Pandit majority area, but we were still living in fear. It was only after we heard that Jagmohan arrived that we had a glimmer of hope. I still remember how one of the army personnel assisted us in making our way out.”

Another Karan Nagar habitant recollects, “I am the youngest of three brothers. My elder brother had been trying to reach home to get me, but he couldn’t before January 20. Ours was a relatively posh area with a Hindu majority population, yet since it was road facing there was regular stone pelting. But the nights of 18th and 19th are unforgettable. The valley was filled with sounds of Kalashnikovs and the loudspeakers on mosques continuously proclaimed, ‘raliv, galiv, ya tsaliv’ (‘convert, flee, or die’). It didn’t seem like there was an option. I remember just resigning to my fate, hiding under the blanket to drown out the sounds, and going to sleep.”

The Janata Dal was in power at the Centre in January 1990, with the Farooq Abdullah government in Jammu and Kashmir working in unison. The party comprised Janata Party factions, the Lok Dal, Indian National Congress (Jagjivan), and the Jan Morcha. The Congress has argued that the BJP was a supporter of the VP Singh government at the time, and therefore, responsible. However, it was an outside supporter, which means that the BJP as part of the Third Front government helped Singh form the government against the Bofors scandal accused Rajiv Gandhi, who was leading Congress (I), without taking any portfolios or being part of the day-to-day functioning. Moreover, Jagmohan has stated on record that he had “pleaded for immediate action” on several occasions to Rajiv Gandhi, since the beginning of 1988.

BJP member and senior journalist MJ Akbar, recounting his interaction about the plight of Kashmiri Pandits with Rajiv Gandhi, said, “The answer was that in Kashmir, the government is that of Farooq Abdullah, and they (Centre) cannot interfere with it.” He continued, “But it is the responsibility of the government to act on such incidents; the Centre cannot turn a blind eye to such horrific episodes.” The saffron party was the one to come through on the removal of Article 370, administering J&K under the constitution of India. The Congress had promised it in its manifesto before but did not follow through. According to political analysts, since the Muslim vote bank always comprised a significant vote share of the Congress, the grand old party could apparently not afford the risk. Interestingly, in the recently concluded Uttar Pradesh state election, the incumbent BJP’s Muslim vote share increased from 2017.

In the 1995 report of the International Commission of Jurists, it was found that the Indian government excluded foreign journalists from working in Kashmir from January to May 1990. The ICJ mission highlighted three categories of breach in human rights. “The first category consists of cases where the Indian Government or its representatives have been exercising powers which are authorised by the local law but do not comply with international norms.” This includes “detention without trial”. The second category covers “torture in the course of investigation of suspects”. The second category, the report says, is the one that garners most publicity but should not “obscure the importance of the first”. The report further states:

“The third category consists of human rights abuses by the militants. Legal purists may argue that human rights are basically rights of individuals against oppression by the State and that, since the militants in Kashmir are not the State, they may be guilty of crimes but cannot be guilty of abuses of human rights. However, in the interests of balance and fairness, the ICJ mission felt that it was impossible to exclude criticism of the actions of the militants from this report.”

The ICJ notes, “Until 1990… there was a significant Hindu minority in Kashmir, totalling some 300,000 people. These Hindus (known as Kashmiri Pandits and mainly of the Brahmin caste) were ethnically and linguistically the same as their Muslim neighbours, being descended from those inhabitants who had resisted conversion to Islam.” The Congress (I) government in the Centre assisted and restricted the ICJ mission in Kashmir, in equal measure at the time. However, the UPA government of this decade seemed to have picked a clear side. On February 17, 2006, Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front commander Yasin Malik was invited to meet Dr Manmohan Singh, the prime minister at the time, where he said that the ‘militant leadership should be involved in the “decision-making” process between India and Pakistan on the Kashmir issue’.

There is no denying that the cause of Kashmiri Pandits can be an election strategy for the BJP. But doesn’t justice begin from the acknowledgement of the crime?

Media Responsibility

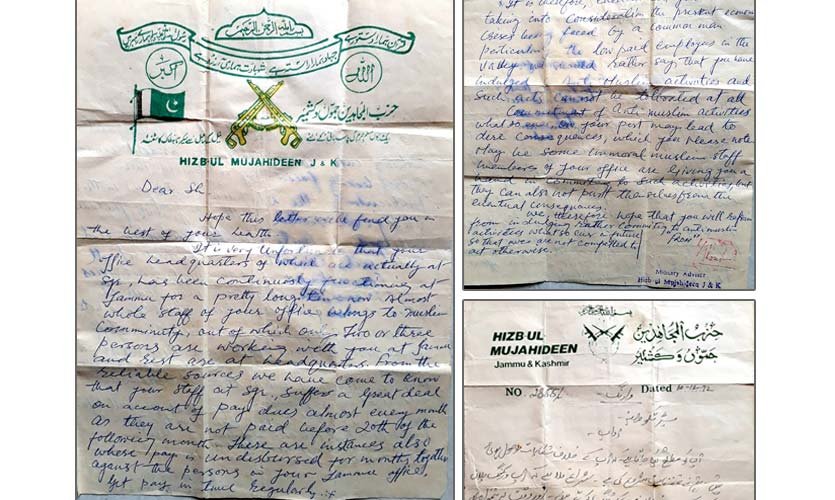

It is virtually impossible to cover the entirety of media and academic bias surrounding Kashmir. However, certain examples cannot be omitted. On May 22, 2017, India Today “dug out” an archive report of JKLF commander Bitta Karate confessing to killing about 20 Kashmiri Pandits himself. Bitta had led the militancy movement, for which he was arrested in June 1990. Jailed under the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act, he was released on bail on October 23, 2006, and has been out ever since. This was the same publication, who invited Yasin Malik to attend the India Today Conclave 2008, as a ‘youth icon’, with Anand Mahindra introducing him as “chairman” of the militant organisation, which has since 1995, “renounced all violence”. Most attacks on Kashmiri Pandits in the erstwhile Jammu district and Kashmir, after 1995, have been attributed to the Hizb-ul-Mujahideen and the Lashkar-e-Taiba.

As the conversation on the massacre of Kashmiri Pandits has garnered attention following the release of The Kashmir Files, on the morning of March 15 yesterday, The Quint put up one of its special coverage posts, asking for help in raising Rs 4,32,000 to support their reporting of the Gujarat 2002 riots.

These events are in addition to what left “academics” like Arundhati Roy have always maintained, “Kashmir has never been an integral part of India.”

Testimonies

“This film shows the horrifying nights not only my family went through but what every Kashmiri Pandit family went through… My father’s sister, Girjia Tickoo, was a librarian at a University who had gone to collect her paycheck, on her way back the bus she was traveling from was stopped and what happened next still leaves me in shivers, tears, and nausea. My bua was then thrown into a taxi, with 5 men (one of them being her colleague), who tortured her, raped her, and then brutally murdered her by cutting her alive with a carpenter saw. Imagine being the brother who had to recognize his Babli, who wasn’t at fault in this gruesome battle of total hypocrisy.

Till this date I’ve never heard anyone from my family speak about this incident. My father tells me every brother lived in such shame and anger that nothing had been done to receive justice for my Babli Bua.”

– Sidhi Raina, member, US Kashmiri Pandit Youth

The character of Sharda Pandit in the film has been based on Sidhi’s aunt Girija Tickoo, and BK Ganjoo’s wife Vijay Ganjoo. The events shown in the film have been confirmed by the kin of both families.

“My uncle was a part of the RSS in Anantnag, and had a meeting with George Fernandes, who was the Union railway minister at the time. Fernandes was in town to find out more about the targeted killings and commission a report, and someone had referred my uncle’s name as he had his ear to the ground.

Next thing we know he is kidnapped, and nobody can find him. I was the one to receive his bullet ridden body, delivered to our doorstep by the JKLF. We had to perform his last rites in a hurry as well so the rest of the family members could make it out safely. My father was already on the hit list stuck outside our house.”

– Kusum Kaul, president, Koshur Samchar, Ahmedabad

“Being a member of the Hindu community and a staunch RSS pracharak, I was one of the many identified and put on the hit list. Circumstances were such that it was too difficult to get me out, so my family had to be sent ahead. After a week, while neighbours we grew up with continued to be in search of our heads, my maternal uncles travelled from New Delhi to shift me out of Srinagar, hidden in a truck with some others who also had a target on their back.”

– Anil Shalli, member, Koshur Samchar, Ahmedabad

“My brother was on the hit list because he was an RSS worker. Until late 1989, we were used to the regular stone-pelting, especially after an India-Pakistan cricket match, and the eve-teasing. But once our community leaders were assassinated, any hope for peaceful co-existence was lost. I saw the lifeless body of Judge Neelkanth Ganjoo in Hari Singh Street market, from the window of the office where I was doing my CA Articleship.

We were not allowed to leave for a while since the militants were still circling his body chanting Azadi. Once calm returned, I made my way home, only to be assaulted by one of the militants with a knife to my neck. That was when I realised that we couldn’t stay.

We had to wait until January 24 till my uncle came from Delhi to get us out. After that, my family and I stayed in their stables meant for horses for a year. My father was on dialysis and could not bear the heat. But we still consider ourselves lucky because it was worse for many others.”

– Vasudha Bhan, member, Koshur Samchar, Ahmedabad

“A little while before migration in January 1990, I started noticing a gradual change in my friends and classmates around me. It started small. The boys started keeping longer beards and the girls who used to interact with us easily stopped associating with us and started wearing burqas. There were times when some would disappear, and people would say they’ve gone for ‘training’. They would return after some time, but I could never ask to confirm. However, I have seen the ‘jihadi’ videos on their VCRs… they used to have it on cassettes at the time… displaying how they were fighting the Russians in Afghanistan. We used to take it very lightly. They were my closest friends, so it seemed liked a get together to watch a movie like Rambo. Then things escalated so quickly that we knew we had to leave.”

– Bownesh Bambroo, member, Koshur Samchar, Ahmedabad

“This is the reality. We have seen this and experienced this first hand. Our people were slaughtered, and we had to flee. Yet our countrymen didn’t seem to know what we were up against. It was considered to be your everyday rioting. My family was lucky enough to have a place to stay in Jammu, but many others I personally know had to stay in tents. There were 16-18 people housed in one tent, with scarcity of medicines and water. These were people with five storey houses, numerous facilities, and infinite supply of water in this place called ‘heaven’.

Under the current government, we have a renewed hope for justice that all our perpetrators will be put behind bars, and those who killed our people… not sparing even children… will be hanged.”

– Sunil Kachru, general secretary, Koshur Samchar, Ahmedabad

The Horus Eye is a weekly column written by Divya Bhan analysing current affairs and policies. This column does not intend or aim to promote any ideology and does not reflect the official position of The Sparrow.

Also read: “Convert, Die, or Flee”: 32 Years Of The 1990 Exodus Of Kashmiri Pandits