We continue to inhabit a country whose political, legal, and social systems are shaped by colonial legacies. Despite the elimination of more than 1200 archaic laws, many obsolete laws still have adherence to how they were when British colonialism was still in effect. The following are some of the laws that continue to shape our lives.

Sedition Law

In the recent past, Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code was applied against two youths of the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) for expressing their support for separatist Afzal Guru. The Hindu explains that throughout the last three years, the provision has been applied to many. In July 2017, the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) recorded 165 arrests on the charges of sedition.

Seditious activities were first prohibited in colonial India in 1835 and were formally criminalised in 1870. In the early days of the law, nationalist leader Bal Gangadhar Tilak was one of the first to be detained. In Pune, some Brahmin youths who were allegedly influenced by Tilak’s public speeches murdered two British soldiers, as per the Bombay High Court’s archive. After being charged with sedition twice, Tilak was released after completing an 18-month sentence for the first trial, and sentenced to six years for an editorial he published in his newspaper Kesari.

In spite of the disappearance of the term sedition from the Constitution, it remains as Section 124A of the IPC.

The Indian Penal Code

The Criminal Procedure and Penal Codes in India have their roots in the 19th century. The Bengal State Prisoners Regulation of 1818 gave way to the Defence of India Acts of 1915 and 1939, respectively. Even before terrorism by outside elements, there was the Preventive Detention Act of 1950, which was used to imprison, prosecute, and punish freedom fighters. Rather than abandoning it, independent India made sure to adopt the act. This act gave birth to the Maintenance of Internal Security Act in 1971, which was resurrected as the National Security Act (NSA) in 1980. The allusion to “national security” was just rhetoric; the act was and continues to be utilised to repress political opposition.

With increasing mass mobilisation and growing public protest to express dissent, we are seeing a renewed zeal to use draconian laws like the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 2019, amended in tandem with Section 124A, and the NSA, 1980 to silence those who disagree, and those who are referred to as tukde-tukde, Khan Market and Gupkar gangs, or urban nazis. Scroll.in explains that a police officer can make an arrest under the current law if they feel it is necessary. Among others, it has been used liberally against protesters, cartoonists, and a local cricket team in Kashmir who sang the national anthem of Pakistan before a cricket match between India and Pakistan in 2017.

Colonising Kashmir

Kashmir illustrates India’s own long history of colonialism, according to the Conversation. The Indian government has also abolished Article 35A of the state constitution of Jammu and Kashmir, making it easier for non-Kashmiris to buy land, hold jobs, and further colonise Kashmir. Hafsa Kanjwal, an assistant professor of South Asian History at Lafayette College has argued that the inflow of Indian settlers is designed to change Kashmir’s demography and may lead to ethnic cleansing, inaugurating India as a settler-colonial state in Kashmir. The news website explains that in explaining its decision to revoke Articles 370 and 35A, India has used the language of counterterrorism that has become so common since 9/11, along with the promise of corporate development. Even if necessary, it is noteworthy that these justifications were derived from colonial times and reframed for the 21st century.

Education System

Before colonial control, India had a highly established educational system, which was maintained for centuries until 1820.

India’s education infrastructure consisted of several models of educational institutions, and teaching in native languages. As V. Ravi Kumar writes in the Destruction of the Indian System of Education, the British effectively wrecked the Indian educational system, rendering one of the most literate nations devoid of sound learning. In consequence, illiteracy in India today is vastly higher than it was a century ago, according to Kumar. By 1820, the British had already destroyed the financial resources supporting our educational system – a process they had been conducting for nearly twenty years, enacting a series of regulations one after another such as standardising the medium of instruction, destroying the Gurukul system.. That was not the end of the story.

British historian and educator T.B. Macaulay was invited to determine how the money should be diverted, who should be privy to education, and how to educate the Indians. English was made the medium of instruction, and the money was diverted for English education. Macaulay decreed that India would receive an education in English, the language of the West, as a result of the British education system.

During the round-table conference in 1931, Mahatma Gandhi categorically mentioned, “The beautiful tree of education was cut down by you British.” The system continues to exist in India, which makes education inaccessible for those unable to afford it.

Personal Laws

During the Medieval era and the Mughal Empire, Muslim authorities preserved peace between Hindu and Muslim laws and opted not to meddle with Hindu family, marriage, and succession rules. Instead of enacting a new law to balance the religious emotions of both populations, India’s Governor-General Warren Hastings cultivated the personal laws for Hindus and Muslims.

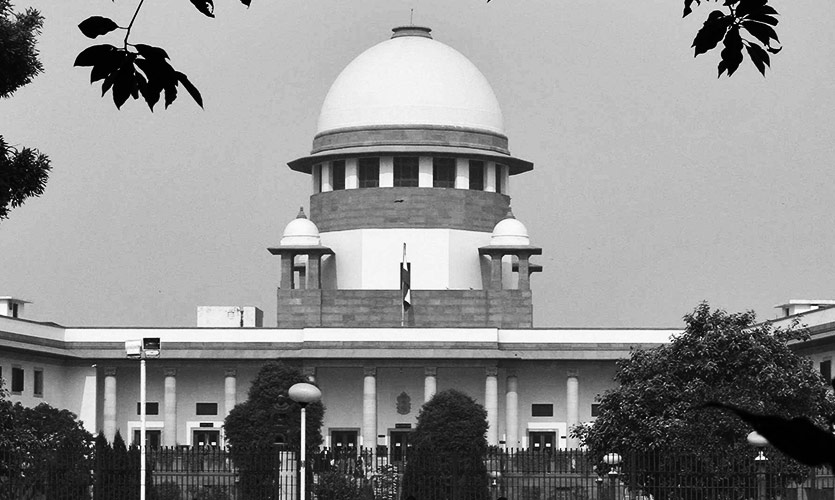

For many years, according to the Indian Express, there have been raging debates over triple talaq under the Muslim personal law. Recently, however, the Supreme Court declared the practice as void and invalid. The Supreme Court urged the government to revise The Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Marriage) Bill, 2017 and introduce laws encouraging gender equality. Assented in July 2019, the act was implemented retrospectively from September 19, 2018.

By law, Indians were forbidden from bringing cases and disputes before the Mayor’s Court (the highest court under British control) and were instead instructed by the Charter Act of 1753 to handle their problems themselves unless both parties agreed to be bound by the rulings of that Court. Personal laws were established in the 17th century as a result of the Hastings Rule, which distinguished between Hindu and Muslim personal laws. This was the impetus for personal laws to gain a firm ground in the 17th century and remain as they are today.

Criminalisation Of Homosexuality

The British introduced Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) as a means to criminalise homosexuality, which was “against the order of nature”. The section has been the subject of much controversy since 2009 after the High Court decriminalised homosexuality. However, in 2013, the Supreme Court ruled that homosexuality is still a crime in India. People were given a glimmer of hope after developments regarding the IPC law in 2018. The Supreme Court, headed by Chief Justice Dipak Misra, heard a number of petitions from July 10-18 without a break. On September 6, 2018, the Court unanimously ruled that Section 377 was unconstitutional and abolished it. However, it was a half victory since same-sex marriages are still not permiited under Indian laws.

The roots of Indian legalities lie in European culture, which was for a long time, an influence on Indian thinking and ways of doing things. According to the Indian Express, in Europe, people not conforming to heterosexuality have been stigmatised since the 11th and 12th centuries when groups such as lepers, witches, prostitutes, and homosexuals were considered carriers of contamination. In Europe, sodomy laws were considered necessary wherever colonisation was practised, as the contamination threatened Europe’s sexual identity. The British Court said that homosexual acts are “vile, foul, filthy, lewd, beastly, unnatural and sodomitic practices”. The defence had objected that the vagueness of the crime did not give clarity to the crime.

England made homosexuality partially legal and repealed its 1885 law, introducing the Sexual Offences Act, 1967, which amended the previous law that criminalised homosexuality.

Read more: Does The Demand For A Uniform Civil Code Overlook India’s Religious Freedom?

Laws that are out of date are still too prevalent in India. The Property Acquisition Act that has been at the centre of the debate over the acquisition of land for big projects on several occasions, dates to 1894. Our Civil Procedure Code dates to 1908, our Evidence Act dates to 1872, and our Telegraph Act dates to 1885. There are a plethora of others.

The Indian Constitution grants the government vast rights to adopt laws that discriminate against individuals based on characteristics such as religion and caste, to limit the freedom of expression, and to limit the right to property. In a nutshell, it allows for intentional political, economic and social exploitation.