In response to a petition filed by a Rajasthan local after a trials court judgment refused his appeal for divorce, the Delhi High Court reiterated the demand for the Uniform Civil Code.

The case shed limelight on the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 (HMA), once again bringing forth the debate over enacting the Uniform Civil Code (UCC) in India, which would mean the precedence of a common law over all, including religious and personal laws. On July 9, Delhi HC Justice Prathiba M. Singh reiterated the Court’s long upheld demand for introducing the UCC, after a petition questioning the relevance of the HMA was brought forward by a divorce case. The couple involved belongs to the Meena community of Rajasthan, which is recognised as a notified Scheduled Tribe. Although majority of those belonging to the Meena community are classified as Hindus, the wife claimed that the HMA did not apply to them as per the exclusion offered under the Section 2 (2) of the Act to the members of the tribe. The trials court agreed, however, the HC maintained that since the marriage was unionised in accordance with Hindu rites, the husband’s petition should be allowed to proceed.

“Codified statutes and laws provide for various protections to parties against any unregulated practices from being adopted. In this day and age, relegating parties to customary Courts when they themselves admit that they are following Hindu customs and traditions would be antithetical to the purpose behind enacting a statute like the HMA, 1955,” said Justice Singh.

The Indian Judiciary’s Position

Article 44 of the Indian Constitution states, “The State shall endeavour to secure for the citizens a uniform civil code throughout the territory of India.” Although comprised in the Constitution, the Article forms a section of Part IV of the document, which outlines the framework for the Directive Principles of State Policy. Article 36 to 51 of the Constitution of India form this segment which is a set of directions to the State (here, “the Government and Parliament of India and the Government and the Legislature of each of the States and all local or other authorities within the territory of India or under the control of the Government of India”) but, not the law of the land.

The judiciary has brought up the need for implementing the UCC time and again, with a popular example being during the Shah Bano case proceedings. The final verdict of the Supreme Court vis-à-vis the Mohd. Ahmed Khan vs Shah Bano Begum And Others (1985) case directed that the maintenance due unto Shah Bano be paid by Ahmed Khan, not only in accordance with Section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure but also with the teachings of the Quran. The Court cited various works in its judgement including Dr. Tahir Mahmood’s book Muslim Personal Law in which he says, “In pursuance of the goal of secularism, the State must stop administering religion based personal laws”.

The court observed that the Aiyats 240-242 analysed from various translations such as Muhammad Zafrullah Khan’s The Quran, Dr. K.R. Nuri’s The Running Commentary of the Holy Quran, Marmaduke Pickthall’s The Meaning of the Glorious Quran, Text and Explanatory Translation, and Arthur J.’s The Quran Interpreted, “leave no doubt that the Quran imposes an obligation on the Muslim husband to make provision for or to provide maintenance to the divorced wife”. It further stated, “The contrary argument does less than justice to the teaching of the Quran.”

The apex court perceived that a common law “will help the cause of national integration by removing disparate loyalties to laws which have conflicting ideologies”.

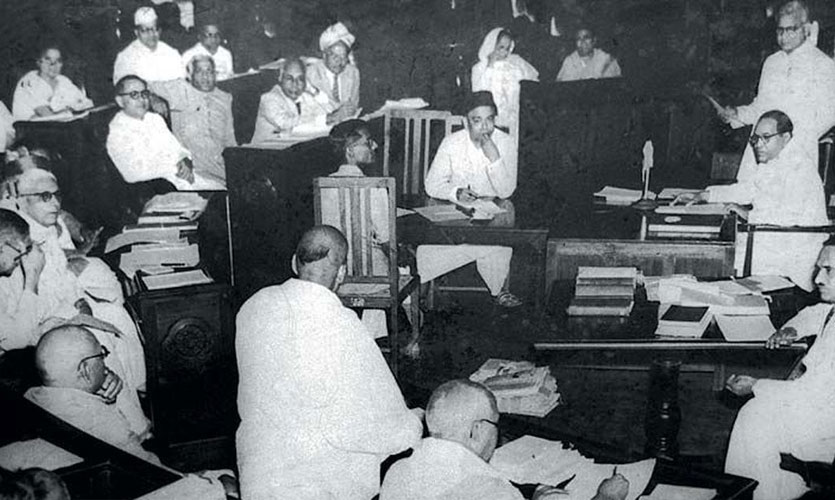

The hostility toward a uniform law for the country has been seen among Hindus as well, with “vehement” opposition from the upper class and orthodox sections of the community. The Hindu Code Bill proposed by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, seeking equality in marriage, divorce, property, inheritance and so on, was stalled by the Parliament owing to rising discontent. Not only did this set back the era of reforms in the country, it also led the ‘Father of the Constitution’ to resign from the Cabinet.

The Dilemma

The UCC has historically made ruling parties in India nervous and hence, has never seen the possibility of implementation. Following the Shah Bano case, the Rajeev Gandhi government nullified the Supreme Court’s judgement by passing The Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986, consequently, resulting in Gandhi being accused of “minority appeasement”.

The most common arguments against the implementation of the UCC, apart from offending respective vote banks, is maintaining the secular fabric of the nation, and protecting people’s right to religious freedom. As law trainee Akshaya Chintala justifies in her paper, the UCC does not mean a common state religion. “The state does not have a religion of its own… and though irreligious is not anti-religious,” she explains.

Shahryaar Salim, a member of the Muslim community in Pune briefly, and Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for over 25 years, says that the UCC should be more of a choice than a compulsion. “As a Muslim, I feel there should be complete freedom for the community to practice the Sharia, however, any issue outside the community bounds should follow the law of the country,” asserts Salim. He goes on to emphasise that it is the increasing bearing of the patriarchal norms of our society that has led to the need for this. “The Sharia respects women’s rights and so does the religion. Unfortunately, the teachings have been manipulated such that their rights have been written off,” says Salim. “In a democracy, if one is not able to find help and support within the community first, then they surely have the right to turn to the government,” reiterating his stance of providing the agency of choice. However, as Salim states, personal laws have been held in higher regard and therefore, provide little assistance for governance in certain civil matters.

A 2016 report by senior journalist Dilip Bobb highlights various instances of personal laws proving a hindrance to justice, which includes “the khap panchayats, the quasi-judicial bodies that pronounce harsh punishments, including honor killings and banishment, based on age-old customs and traditions” in Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and Rajasthan. The decisions made by these bodies are still binding despite the Supreme Court’s condemnation. The Haryana government refused to ban them, declaring them as serving a “useful social purpose”. Bobb also brought forth the example of the Jain community and its fasting customs, which led to the death of a teenage girl in October 2016. The validity of the Chotanagpur Land Tenancy Act, 1908, which restricts the jungle’s land cultivation rights to male descendants, has also been questioned by the women of the Oran and Ho communities of Jharkhand. Although, in a controversial move, the state’s BJP government amended the Act to allow the use of the land for non-agricultural purposes in 2017.

During the proceedings of the Constituent Assembly of India Debates (Volume 7) in December 1948, Dr. Ambdekar in his argument for implementing the UCC said, “I personally do not understand why religion should be given this vast, expansive jurisdiction so as to cover the whole of life and to prevent the legislature from encroaching upon that field. After all, what are we having this liberty for? We are having this liberty in order to reform our social system, which is so full of inequities, so full of inequalities, discriminations and other things, which conflict with our fundamental rights. It is, therefore, quite impossible for anybody to conceive that the personal law shall be excluded from the jurisdiction of the State.” Explaining further that this does not mean doing away with personal laws, Dr. Ambekar further clarified, “…no one need be apprehensive of the fact that if the State has the power, the State will immediately proceed to execute or enforce that power in a manner that may be found to be objectionable by the Muslims or by the Christians or by any other community in India.”

The code was not considered a talking point by any party looking to be elected until seven years ago. Prior to the general elections in 2014, the BJP’s manifesto voiced its intention to implement the code. The party’s manifesto stated, “[The] BJP believes that there cannot be gender equality till such time India adopts a Uniform Civil Code, which protects the rights of all women, and the BJP reiterates its stand to draft a Uniform Civil Code, drawing upon the best traditions and harmonizing them with the modern times.” This was also reaffirmed in the party’s 2019 manifesto. Given the sentiment of systematic oppression of the minorities attached with the current government, however, especially following its announcements of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 (CAA) and the National Register of Citizens (NRC), this has not been well received. The Modi government’s recent inclusion with the likes of Brazil and China in terms of the freedom of the press and the controversial implementation of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Amendment Act, 2019, which has seen only a two percent conviction rate, but a 72 percent rise in arrests as per the latest the National Crime Records Bureau data.

Legal experts have informed time and again that the implementation of the UCC will not do away with religious freedom or its secularity. Then again, an order of such impact passed by a Hindu nationalist government, bound to affect the Muslim community the most, will inevitably have dire consequences on the country’s peace and harmony if it is rushed or falls prey to misinformation. Nevertheless, this is provided that first and foremost, the fine print of the code is just and fair and upholds India’s national integrity with equal fervour for all communities.

The Horus Eye is a weekly column written by Divya Bhan analysing current affairs and policies. This column does not intend or aim to promote any ideology and does not reflect the official position of The Sparrow.

Also read: India Needs A Stronger Opposition, But The Congress Is Not It

Also read: India And The Global Trend Of Qualms Against The Press’ Freedom