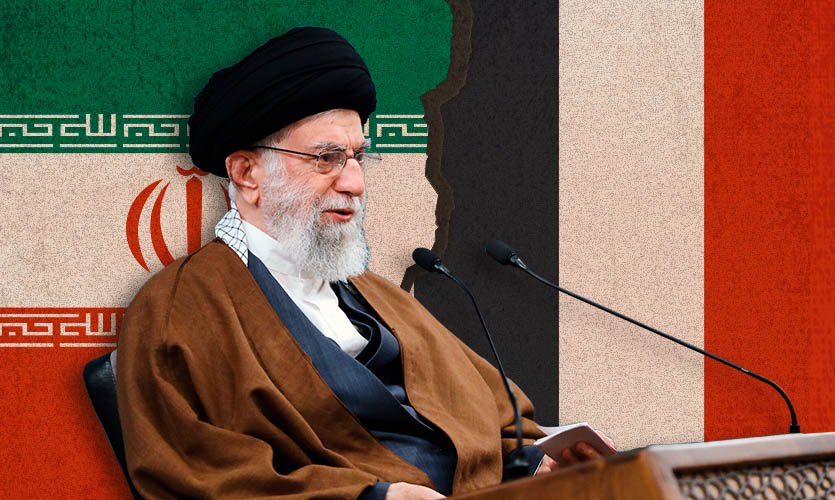

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran’s supreme leader, was allegedly insulted by cartoons published by French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, on Wednesday, following which the country warned France of retaliation.

As part of a competition it launched in December to support the three-month-old anti-hijab movement, the weekly publication published dozens of cartoons ridiculing the highest religious and political figure of the Islamic Republic.

“The insulting and indecent act of a French publication in publishing cartoons against the religious and political authority will not go without an effective and decisive response,” tweeted Iran’s Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian. “We will not allow the French government to go beyond its bounds. They have definitely chosen the wrong path,” he added.

Iran’s foreign ministry announced later on Wednesday that French Ambassador Nicolas Roche had been summoned. “France has no right to insult the sanctities of other Muslim countries and nations under the pretext of freedom of expression,”said Iran’s Foreign Ministry spokesman Nasser Kanani. “Iran is waiting for the French government’s explanation and compensatory action in condemning the unacceptable behaviour of the French publication,” he added.

Meanwhile, France’s ambassador to Iran was called by Kanani, who informed him that France did not have the right to justify contempt towards the “sanctities of other countries and Islamic nations under the guise of freedom of expression”.

The foreign ministry stated in a statement announcing the closure of the French Institute of Research in Iran that it was also assessing cultural connections with France and French cultural initiatives in Iran. The institute, which is linked with the French Foreign Ministry, was formed in 1983. It had been shuttered for many years before being reopened under Hassan Rouhani’s administration, from 2013 to 2021.

The controversial caricatures were published in a special edition of Charlie Hebdo to mark the anniversary of the deadly attack on its Paris office, which killed 12 people, including some of its best-known cartoonists. “Eight years later, religious intolerance has not said its last word,” said its director. “It continues its work in defiance of international protests and respect for the most basic human rights.”

In the issue, Khamenei and fellow clerics were depicted in a variety of sexual images. There were other cartoons that demonstrated the authorities’ use of capital punishment in an effort to quell protests. “It was a way to show our support for Iranian men and women who risk their lives to defend their freedom against the theocracy that has oppressed them since 1979,” Charlie Hebdo’s director Laurent Sourisseau, known as Riss, wrote in an editorial. According to him, all published cartoons defy the authority claimed by the supposed supreme leader, and his servants and henchmen.

Emmanuel Macron’s former minister of foreign affairs, Nathalie Loiseau, called Iran’s response an “interference attempt and threat” to Charlie Hebdo. “Let it be perfectly clear: The repressive and theocratic regime in Tehran has nothing to teach France,” she said.

Charlie Hebdo’s approach has been divisive even within France, seen by supporters as a defender of free expression, and by others as overly aggressive. However, the country was united in mourning when it was targeted in the horrifying January 2015 attack by Islamist gunmen who claimed to be retaliating for the magazine’s choice to publish caricatures of Prophet Mohammed.

When questioned about the dispute, US State Department spokesman Ned Price told reporters in Washington that America was “on the side of freedom of expression”, whether it be “in France, in Iran, or anywhere in between”.

Khamenei, the revolutionary leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s successor, has been appointed for life. Above and beyond daily politics, it is illegal to criticise him within Iran. In 1989, Khomeini famously issued a fatwa, or religious decree, ordering Muslims to murder British-Indian novelist Salman Rushdie for what he saw as the irreverent character of his book ‘The Satanic Verses’. When the writer was attacked at a New York event last year, many activists suspected Iran, but Tehran denied any involvement.

Three months of protests spurred by the death of Mahsa Amini, an Iranian Kurd detained for allegedly breaching the country’s stringent dress code for women, have rattled the Iranian leadership. Iran Human Rights, an organisation headquartered in Oslo, claims that in response, the country has carried out a crackdown that has resulted in at least 476 deaths during rallies, which Iranian authorities typically refer to as “riots”.

The women-led protests against Iran’s religious establishment began in September 2022, following Amini’s death, after she was seized by the “morality police” for reportedly wearing her hijab, or headscarf, “improperly”. Authorities have framed the protests as foreign-backed “riots”, and have used fatal force in response.

According to the Human Rights Activists News Agency, at least 516 protestors have been murdered and 19,260 others have been detained thus far. Two of those imprisoned were hanged last month following trials that human rights organisations described as a travesty of justice.