Desmond Mpilo Tutu, a leading advocate for peaceful reconciliation under black majority rule, died at the age of 90 on Sunday. He led the movement to bring down apartheid in South Africa with his remarkable pulpit and oratory skills.

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa announced Tutu’s death. He said, “Desmond Tutu was a patriot without equal; a leader of principle and pragmatism who gave meaning to the biblical insight that faith without works is dead.” Describing Tutu, Ramaphosa said, “A man of extraordinary intellect, integrity and invincibility against the forces of apartheid, he was also tender and vulnerable in his compassion for those who had suffered oppression, injustice and violence under apartheid, and oppressed and downtrodden people around the world.”

In a statement, the Nelson Mandela Foundation praised Tutu for his contribution to fighting injustice locally and globally, and said that his thinking about making liberatory futures for human societies led to such contributions. “He was an extraordinary human being. A thinker. A leader. A shepherd.”

Archbishop Tutu died of cancer, according to the Desmond and Leah Tutu Legacy Foundation, at a care facility. The first time he was diagnosed with prostate cancer was in 1997, and was hospitalised several times in the following years.

Desmond Tutu was born on October 7, 1931 in Klerksdorp, in what is now the North West Province of South Africa. His mother Aletha was a domestic worker, while Zachariah, his father, taught at a Methodist school. In Desmond’s case, his baptism was Methodist, but he later joined the Anglican Church with all his family members. His family moved to Johannesburg when he was 12, and his mother went to work as a cook in a school for the blind.

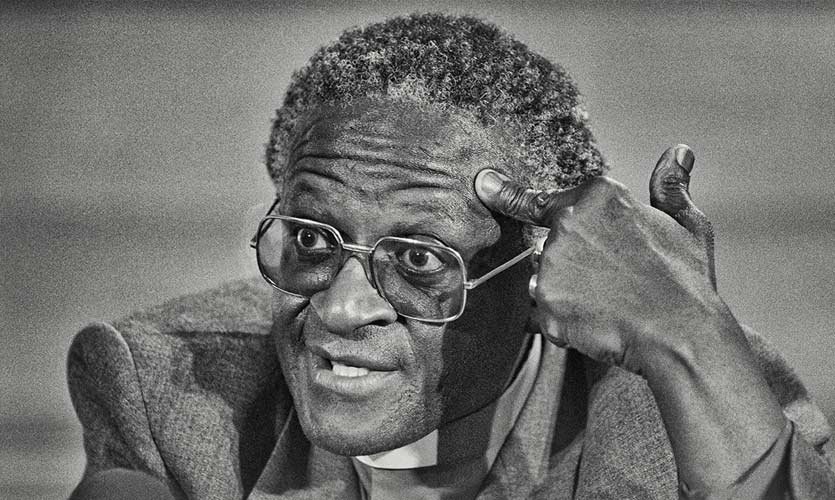

Just five feet five inches tall and with an infectious giggle, Tutu travelled tirelessly through the 1980s to become the face of the anti-apartheid movement abroad while many of the leaders of the then rebel African National Congress, including future president Nelson Mandela, were behind bars. When Mandela became South Africa’s first black president in 1994, Tutu was appointed by him to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission tasked with investigating both white and black crimes during apartheid.

Tutu is credited with coining the term Rainbow Nation to describe South Africa’s ethnic mix after apartheid. In his later years, however, he expressed regret that the nation did not coalesce in the way he desired. Tutu was ordained a priest in 1960 and served as the bishop of Lesotho from 1976-78, assistant bishop of Johannesburg and rector of a parish in Soweto.

His appointment to the episcopacy in Johannesburg was in 1985, immediately followed by his appointment as the first black Archbishop of Cape Town the following year. With his high-profile position, he used his platform to speak out against the oppression of black people in his home country, always claiming religious motives, not political ones. His voice became a powerful force for non-violence in the anti-apartheid movement, earning him a Nobel Peace Prize.

In his sermons, Archbishop Tutu preached that apartheid was as dehumanising to oppressors as it was to the oppressed. He urged economic sanctions against the South African government to force a change of policy at home and opposed violent escalation abroad. While he had expressed disapproval of the apartheid-era leadership, he was equally critical of the ANC, which came to power in the first fully democratic election in 1994 under Nelson Mandela.

Against President Thabo Mbeki, Mandela’s successor, the archbishop accused him of pursuing policies that enriched a tiny elite while “many, too many, of our people, live in gruelling, demeaning, dehumanizing poverty”.

Although Tutu and Mbeki reconciled, – they were photographed together in 2015 as Mbeki, the former president at the time, accompanied Archbishop Tutu to a hospital – he remained dissatisfied with the state of affairs in his country under Jacob G. Zuma’s administration. Zuma denied Mbeki another term despite being embroiled in scandal.

In 2011, when the ANC was accused of corruption and mismanagement, Archbishop Tutu lambasted the government again in terms that were once unimaginable.

Read more: Barbados Renounces British Monarchy, Declares New Republic

He was a spellbinding preacher for much of his life, his voice sonorous and high-pitched at the same time. On many occasions, he embraced his parishioners from the pulpit. The punctuation of his message with wit and laughter, which became his trademark, invited his audience to share in a jubilant bond of fellowship and would sometimes break into dance. In addition to assuring his parishioners of God’s love, he exhorted them to be nonviolent in their struggle.

The teachings of his religion were infused with politics. In addition to his effervescence he was an international celebrity due to his moral leadership. His apparent conviction regarding the virtues of modesty prevented him from acclimating to the perquisites of fame and high office. Always on time, he expressed appreciation to bellhops and maids sent to serve him, and he wasn’t comfortable with limousines and police escorts.

Despite experiencing apartheid’s horrors and indignities, Archbishop Tutu did not give in to the hatred of his enemies. In his youth, he said, he was fortunate to know white priests, and he remained optimistic throughout the long struggle.