The fact that clothing forms an important part of our cultural identity is undeniable, but what is often overlooked is — how this cultural identity gets impacted by our social, political and economic circumstances.

Over the years, Indian clothing has undergone a severe transformation. Our current sartorial sensibilities are an amalgamation of Huns, Greeks, Mughals and British, all of whom have ruled India at some point in history. Although there is a significant contribution of other cultures in creating India’s current cultural wardrobe, the British remain the chief source of influence. Britishers not only managed to change our ideas of proper dressing, but also the fundamental reasons for dressing up in a certain manner. They had their own motivations to introduce them, the primary ones being the increase in monetary benefits and political influence.

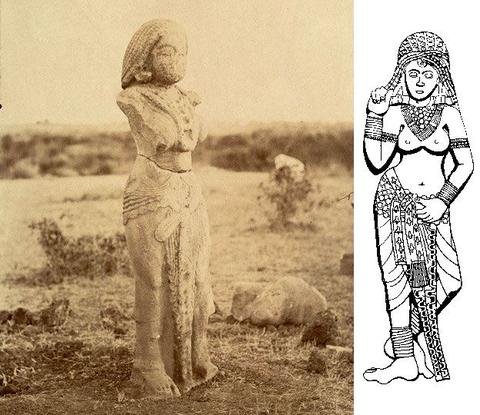

Before the Britishers arrived in India, according to fashion historian Toolika Gupta, Indian costume comprised, “the three draped garments common to both the sexes – Antariya (the lower garment), Uttariya (the upper garment) and Kayabandh (which was like a belt to keep Antalya in place).” It was the reign of Guptas that introduced stitched garments like choli and Ghaghra, worn by women, for the first time in India’s fashion history. The arrival of Islamic rule in the 8th century AD brought stitched garments like kurta and salwar for men in India.

Europeans, who came to India for the first time in the 16th century, as traders, were initially over-dressed for the hot and humid Indian climate. Before they turned India into the crown jewel of the Empire, they were happy to adopt Indian clothing as a more practical choice. It was around the 18th century, when the East India Company, an economic enterprise, focused exclusively on maximising its profit, decided to control more than Indian spices and started interfering with the governance. It was at this point that the British established themselves as superior figures. And, a sense of white superiority underlining their official and unofficial treatment of Indians grew.

Due to this reason, a lot of Indians (mainly the younger demographic) voluntarily adopted British attire such as suits and hats. It was the easiest way for them to feel close to the superior beings they were being ruled by.

Another demographic English clothes gave a sense of empowerment to, were the ones belonging to the lowest castes. A dark shadow of the caste system has always loomed over India and adopting British clothes gave the people at the lowest end of this system a chance to come out of this shadow of their caste, which they were simply born into.

“It may be noted that while Gandhi gave up his western attire during the struggle of independence to drive his point home, Baba Sahib Ambedkar (who shaped India’s constitution, but was from the lower caste), is always seen in the Western Suit, as it gave him the feeling of power,” states Toolika Gupta in her paper The Influence of British Raj on Indian Fashion.

Adding to the social factors were the economic factors that made Indians choose British clothes over Indian clothes. The cost of an English, stitched, factory-made trouser was far less compared to that of hand-spun, hand-stitched cotton clothes made in India. It only made sense for the Indian populace to buy cost-effective English clothing.

It was only after the revival of khadi, in the hands of Mahatma Gandhi, that Indians decided to return to their roots and started boycotting the British clothes. At this point, clothes became synonymous with a nationalistic identity and stood for more than just the class or caste of the person wearing them. They became a political tool — representing an ideology, something Indians had never experienced before. During the freedom struggle, khadi became an important symbol of self-reliance and self-rule, an ideology Mahatma Gandhi wore through his look of the hand-spun, cotton dhoti.

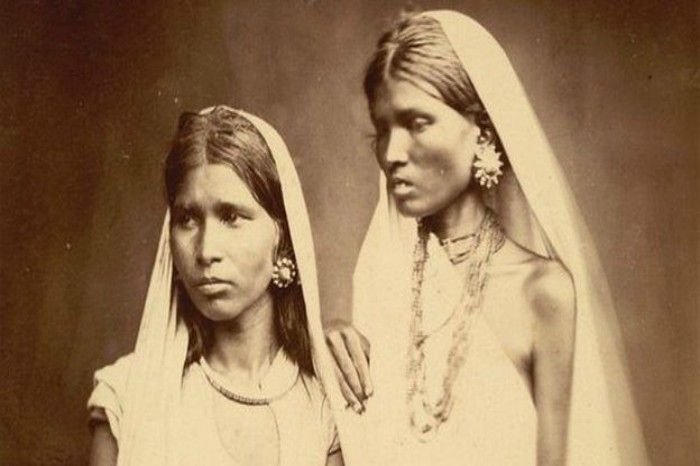

While men were either embracing or rejecting the English clothes based on their political ideologies, no such choice was granted to women. Their bodies and the issue of how to cover them became an ideological battleground between two different cultures. In the chapter, Clothes, Clothes and Colonialism from his book European Intruders and Changes in Behaviour and Customs in Africa, America and Asia before 1800, Bernard S. Cohn explains, “how British and Indian conceptions of modesty were in marked contrast with one another,” while the British had strict codes of morality and respect attached to their clothes, Indians were relatively free in their approach.

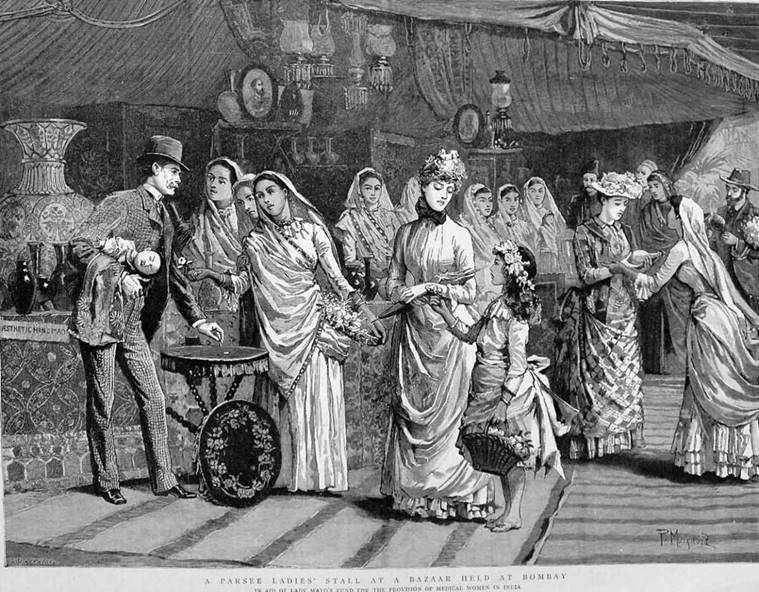

It was the British “memsahibs” who often came to India in search of a groom that became models of virtuous women, whom Indian women were expected to emulate. With their Victorian blouses, multi-layered petticoats, corsets and hats they were the epitome of English modesty. In contrast, Indian women with their bare breasts and a voluptuous figure (which they proudly displayed in a saree) were too scandalous for the British.

Cohn goes on to elaborate in his book, how Britishers in the Southern part of India converted an entire lower caste community called Nadars into Christianity. Nadar women wore saris with no blouses underneath, but under the “civilising package” of Christian missionaries, they needed to be respectably dressed and cover themselves.

Many factors including social, economic, political and religious contributed to the British influence on Indian clothing. The depth and power of this influence can only be understood by analyzing how they not only managed to alter our daily sartorial choices, but also the idea of clothes being much more than mere bodily adornments and coverings.